A few days ago, as my youngest son was heading in to the house after helping with some fall cleaning outside, he stopped and was staring at something. There was a dead bird lying on the ground in front of our neighbor’s house. He asked my wife to bring him a pair of gloves. She told him to just leave the bird alone because he had no idea how it died or what kind of diseases it may have. He kept persisting and said that he really needed a pair of gloves so that he could give it a proper burial. Great kid, right? He’s got such a warm and caring heart. She asked him why he was so insistent on burying the bird. He proceeded to explain to her that, if he was kind enough to bury the bird and give it a small headstone and maybe say a few words over it that the bird might come back down the road as a person and give him something in return and make him rich. This is a popular theme in Japanese fairy tales when a poor, usually older couple who can barely make ends meet, help an injured animal that eventually dies and later comes back to give them riches. When she started telling me this story I thought, “Awww, that’s my boy.” By the time she was done, I was like, “Yep, that’s my boy.”

A few days ago, as my youngest son was heading in to the house after helping with some fall cleaning outside, he stopped and was staring at something. There was a dead bird lying on the ground in front of our neighbor’s house. He asked my wife to bring him a pair of gloves. She told him to just leave the bird alone because he had no idea how it died or what kind of diseases it may have. He kept persisting and said that he really needed a pair of gloves so that he could give it a proper burial. Great kid, right? He’s got such a warm and caring heart. She asked him why he was so insistent on burying the bird. He proceeded to explain to her that, if he was kind enough to bury the bird and give it a small headstone and maybe say a few words over it that the bird might come back down the road as a person and give him something in return and make him rich. This is a popular theme in Japanese fairy tales when a poor, usually older couple who can barely make ends meet, help an injured animal that eventually dies and later comes back to give them riches. When she started telling me this story I thought, “Awww, that’s my boy.” By the time she was done, I was like, “Yep, that’s my boy.”

Everybody aspires to something. I can’t imagine that there are many people who just go through life completely aimlessly with no particular rhyme nor reason. Most of us grow up wanting to be great in our own way and the most common vision of greatness comes in the form of leadership. CEO, president, general, whatever the organization, few people aspire to stay at the bottom of the totem pole. But why is this? What’s their motivation for wanting to get to the top? Undoubtedly, some start with a noble vision of affecting change for the good of humanity, but I would venture to say that for the majority of folks aspiring for the C-suite, it is just a matter of pride.

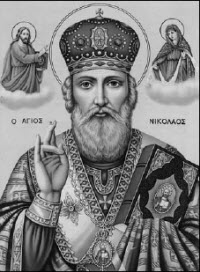

The clergy/priesthood is no exception in this regard. Priests ordained in great cathedrals likely aspire to be cardinals some day and even in many protestant churches, men and women dream of some day being bishop. Even in some non-denominational churches pastors will plant a church with the goal of some day being the next Joel Osteen or Bill Hybels. Oftentimes, while a few token efforts are made, there is a complete disregard for the needs of people. At worst (and yes, this happens, too), pastors of some mega churches will feed on the needs of the hurting and oppressed to help them build their ecclesiastical empires. There is a pervading mindset in any area or industry of, “What’s in it for me?” and unfortunately, the church is not above this. Sometimes another’s pain or loss is used by people to their own advantage. Even Jesus’ own disciples are not above being overly concerned for numero uno.

In Mark 10, Jesus and the disciples are heading in to Jerusalem and I picture a sort of child-like excitement on the part of the disciples almost like going up the yellow brick road to Oz. “We’re going to Jerusalem, woo hoo!” But Jesus corrects them and says, “You do realize that this is no vacation. When we get there I’m going to be handed over to the authorities, mocked, spit at, tortured, and killed, but on the third day I will rise.” And then this is the best part, James and John say, “Wow, that’s a bummer. Yeah, that’s really rough. Oh hey, by the way, we want you to do something for us.” “And what would that be?” “Well, we were thinking, you know, you could do us a solid and let us sit on either side of you in your glory.” The very people hand picked by Jesus shrug off the fact that he is about to be killed and focus instead on what they can get out of the situation.

Jesus of course has a comeback because throughout the gospels, people can’t seem to take the hint that you just don’t ask Jesus questions because he will never fail to be a buzzkill. “Can you drink the cup that I drink?” We can see the way Jesus evolves in the gospels by the way he asks the question. In Matthew, when James and John’s mother ask Jesus to let them be at his right and left, he asks them if they can drink the cup that he is about to drink. In Mark, it is the cup that Jesus already drinks. It’s easy then to read the Matthew version and see this as Jesus talking about his crucifixion and death. I think Mark is more accurate, however. Jesus tells James and John that these seats at his right and left are reserved for those who deserve them and he cannot just give them away at random. Those who occupy those seats will deserve them because they drink the cup that Jesus drinks – devoting themselves as servants for the good of other humans. The rulers that they are used to – the Gentile Roman rulers – rub it in and treat their subordinates like dirt. But you, if you want to be great, if you want to consider yourselves my people, you will serve others with no thought of praise or notoriety.

This is a great example of servant leadership. Jesus shows the disciples that to be a great leader, you have to have something worth leading for. Not personal fame. Not your own prosperity. Instead, to be a great leader, you have to be a servant who is willing to set your own ambitions and pride aside for the good of others.

In 1891 a young Indian man graduated law school in England and moved back to his home country. Not being able to get work, he moved to South Africa and was on track to become a rather successful attorney. During one of his cases he attempted to get it settled out of court and was successful in doing so. This case would change the course of the young man’s life because he said he had learned the true practice of law because he had seen the better side of human nature and the good that lies within the human heart. He decided to dedicate his life to solving major problems by appealing to the good side of human nature and bringing about peace amidst conflict without fighting in a practice that came to be known as non-violent resistance.

He moved back to India which was under British occupation and rule. After many years, his servant-like leadership proved successful when the British finally gave up and in 1947 left India. This man chose to give up the fame and wealth that lay certain in front of him. He could have pursued politics and potentially amassed an army to try driving out the British. Instead, he chose to be like the least of these and led from the trenches. The result was victory without bloodshed. Well, almost. This great servant leader was assassinated a year later when trying to use the same tactics to bring about peace between the Hindus and the Muslims. On the day of his death, for the first time ever for a non-political figure, nations around the world lowered their flags to half mast for the man who was known as Mahatma, meaning “great soul.” He had taught the world what it looked like to be a true leader. Having never owned a great corporate empire nor governed a great nation, Mahatma Gandhi had found something worth leading for – the well-being of the human race.

I see that same spirit at IUCC. This is why I’m proud to be here. I am NOT in the business of putting down other churches and other denominations because beyond a doubt, there are some churches in all denominations that are doing wonderful things for the people in God’s great creation. What I AM in the business of doing though is looking around at this congregation and smiling with pride because we are a church that serves God’s people, not because there is necessarily something in it for us, but because we live by the example that Jesus set and because it’s just the right thing to do.

In a Zen koan that is attributed to the 9th century Buddhist master Lin Chi, it is said if a Buddhist meets the Buddha on the road, he or she should kill him. Other versions of this story take place with a conversation where the master is teaching the student a valuable lesson. What lesson is it? The master teaches his student that whatever conceptions one has of the Buddha, they are wrong and as a result they impede the path to enlightenment. If the practitioner’s mind is wrapped around a particular view of Buddha and his teachings, then all other possibilities become impossibilities. This is no different in the Christian church when we consider the person of Jesus.

In a Zen koan that is attributed to the 9th century Buddhist master Lin Chi, it is said if a Buddhist meets the Buddha on the road, he or she should kill him. Other versions of this story take place with a conversation where the master is teaching the student a valuable lesson. What lesson is it? The master teaches his student that whatever conceptions one has of the Buddha, they are wrong and as a result they impede the path to enlightenment. If the practitioner’s mind is wrapped around a particular view of Buddha and his teachings, then all other possibilities become impossibilities. This is no different in the Christian church when we consider the person of Jesus.